I’m not a gamer. I haven’t played many games on my phone in years. But last weekend, something nostalgic nudged me to download Tetris. It seemed like a harmless escape, a throwback to a simpler time.

Recently, I’ve been thinking a lot about how technology affects us. I just completed my certification with the Center for Humane Technology and have been diving into books like Stolen Focus by Johann Hari and The Anxious Generation by Jonathan Haidt. These have made me acutely aware of the subtle and sometimes not-so-subtle ways digital systems manipulate our attention and choices. So, as I played Tetris, I analyzed what I was experiencing.

What I thought would be a fun, stress-free game quickly revealed itself to be something else entirely: a system designed not just to entertain but to extract as much value from me as possible.

The Game Starts Simple—Then the Manipulation Kicks In

At first, it was perfect. The classic gameplay of arranging falling blocks into lines felt satisfying and nostalgic. But by the time I reached level 10, everything changed. Ads started popping up—often. They weren’t just random ads but for other games that looked suspiciously like Tetris.

Each ad allowed me to experience a snippet of gameplay, highlighting addictive mechanics like the ones that make Tetris so engaging:

simple challenges

quick rewards

a sense of progression

Participating in these ads felt like looking into a mirror of my habits. The message was clear: "If you like Tetris, you’ll love this!"

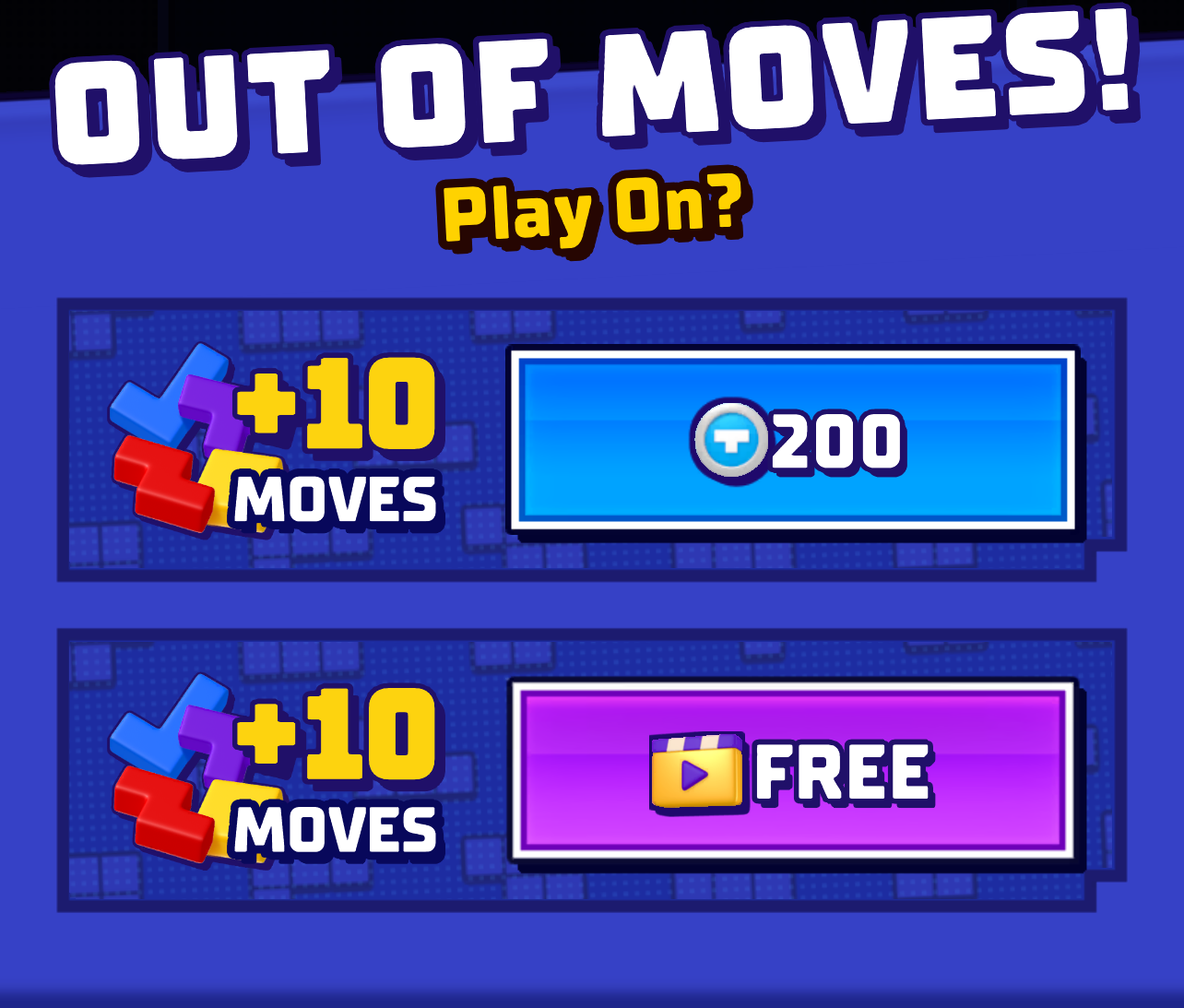

But the real kicker came when I was forced to choose: watch a 30-second interactive ad for one of these games or pay to remove ads entirely. The choice wasn’t fair or neutral. It was a carefully engineered friction point designed to wear me down and push me toward spending money or diving deeper into the endless loop of game ads.

Why Are the Ads So Targeted?

These ads weren’t randomly selected. They were designed to feed off the very traits that drew me to Tetris in the first place:

Familiar Mechanics: The ads showcased games with similar puzzle-like challenges, making them instantly appealing.

Frustration Exploitation: Ads appeared right after I made progress, disrupting my flow and leaving me impatient to get back to playing.

Engaging Mini-Games: Some ads forced me to interact—move pieces, solve puzzles—as if I were sampling the next game I’d inevitably download.

It was a masterclass in psychological manipulation, leveraging my engagement with Tetris to steer me toward other games in the same ecosystem.

The Cost of “Free” Isn’t Just Money

This experience made me reflect on the broader implications of these practices. On the surface, Tetris is a free game. But the reality is that the cost isn’t zero:

Your Time and Focus: The ads are designed to capture your attention, pulling you away from the game itself.

Your Patience and Autonomy: The constant interruptions and forced choices chip away at your ability to feel in control.

Your Wallet: The ultimate goal is to nudge you toward spending money, whether it’s on Tetris or the games being advertised.

It’s not just about Tetris—it’s about how the entire ecosystem of free-to-play games operates. These systems are built to maximize engagement, often at the expense of our well-being.

What This Means for the Attention Economy

Tetris and its ad-driven strategy are a microcosm of a more significant problem. The attention economy thrives on keeping us hooked, offering a fleeting sense of control while pulling the strings in the background. This mirrors the tactics of social media platforms, retail apps, and even news sites.

The ads in Tetris reveal the full cycle: one game leads to another, and another, creating an endless loop of engagement and extraction. It’s a system where our attention is commodified, our choices manipulated, and our patience worn thin.

How We Can Do Better

As someone who cares deeply about the ethics of technology, I can’t help but wonder: what would it look like to design games and ads that respect users?

Transparency: Clearly disclose how and why ads appear, and offer fair alternatives without coercive friction points.

Ethical Ads: Instead of exploiting frustration, ads could highlight features users genuinely value, without manipulating emotions.

Humane Design: Build games that respect the player’s time and autonomy, balancing engagement with opportunities for rest and intentionality.

Conclusion: A Lesson Hidden in the Blocks

Downloading Tetris last weekend gave me more than nostalgia—it gave me a front-row seat to the mechanics of the attention economy. What seemed like innocent fun was a system designed to keep me playing, paying, and consuming.

The experience reinforced what I’ve learned about the power of ethical design. Games like Tetris don’t have to be manipulative to succeed. They can entertain, challenge, and delight without exploiting our attention or wallets.

It’s time we demand better. If we can build games that respect players as much as they entertain, we can move toward a digital ecosystem that values people over profit. That’s a game worth playing.