The Delusion of Objectives

The world is filled with innovations and high-flying ideas that were the result of objective-less discovery, but in the world of work, nothing gets launched till it's tied down to an objective.

TL;DR: Modern marketing and innovation are often constrained by the assumption that progress is best defined through objective-based achievements. Our world is structured around setting targets and measuring improvements. However, this fixation on objectives can distort and prevent a better understanding of desire, incentives, and the true nature of innovation.

An Objection to Objectives

Consider how often you have aimed for a specific objective and succeeded exactly as planned. More often than not, you land somewhere near it—or in an entirely unexpected place—only to discover something novel.

Maybe you’ve seen movies like Jerry Maguire, Groundhog Day, Toy Story 2, The Wolf of Wall Street, Whiplash, The Dark Knight, or Citizen Kane, that all illustrate a perennial truth we feel to our core; dogged determination toward an objective is not the only path to achieving greatness.

Science provides many historical examples of groundbreaking innovations that arose from mistakes and exploration.

William Perkin’s failed quinine experiment led to the first synthetic dye.

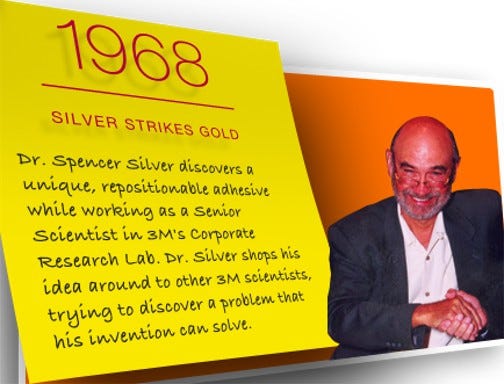

Spencer Silver’s weak adhesive gave rise to the Post-it note.

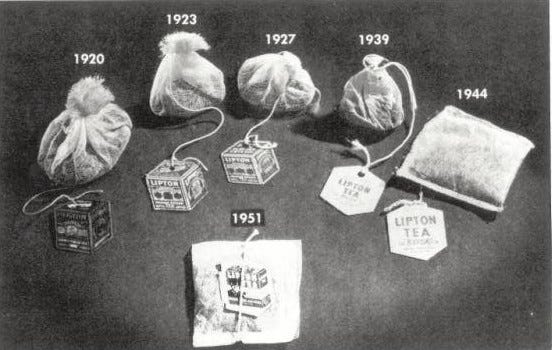

A packaging error by Thomas Sullivan created the tea bag.

Wilhelm Röntgen discovered X-rays by accident,

Percy Spencer’s melted chocolate bar led to the microwave oven.

The Wright Brothers relied on Otto’s work on the combustion engine. The invention of computers by Atanasoff depended on Fleming’s discovery of vacuum tubes. Chuck Berry’s rock and roll would not exist without Scott Joplin’s jazz.

These innovations were not the result of rigid goal-setting but of flexible thinkers willing to follow curiosity and unexpected opportunities.

There are countless examples of how truly amazing innovations were not the result of strict goals, but a result of flexible thinkers and individuals willing to follow their interest for the interests sake alone, and to look for the next stepping stone.

Whether on a Hollywood set, a laboratory, meeting space, or within our lives, we need to accept that dramatic and innovative breakthroughs come more often, and more freely, from open-ended exploration rather than narrow, objective-based pursuits.

But I bet you’re still thinking, “Jake, my guy, objectives are real and good.” And I’m not gonna argue with you, but I am gonna keep blogging about it, so, keep listening.

The Problem with Objective-Based Thinking

In reality, it isn’t objectives themselves that’s bullshit, they are just tools, points on a chart. The real problem is the behaviors and bad thinking objective-based thinking unleashes.

In marketing, when a business or client sets a goal, marketers lay out steps to achieve it and take action. Work toward that goal is often disrupted by real-world unpredictability. There has to be flawless execution across multiple stakeholders and interconnected platforms and technical infrastructure, unchanging customer behavior and rising capital, and stable market conditions and smooth supply chains.

If you squint, you realize objective-based goals are very fragile and have to flex and function within the constraints of the environment and energy levels they exist in.

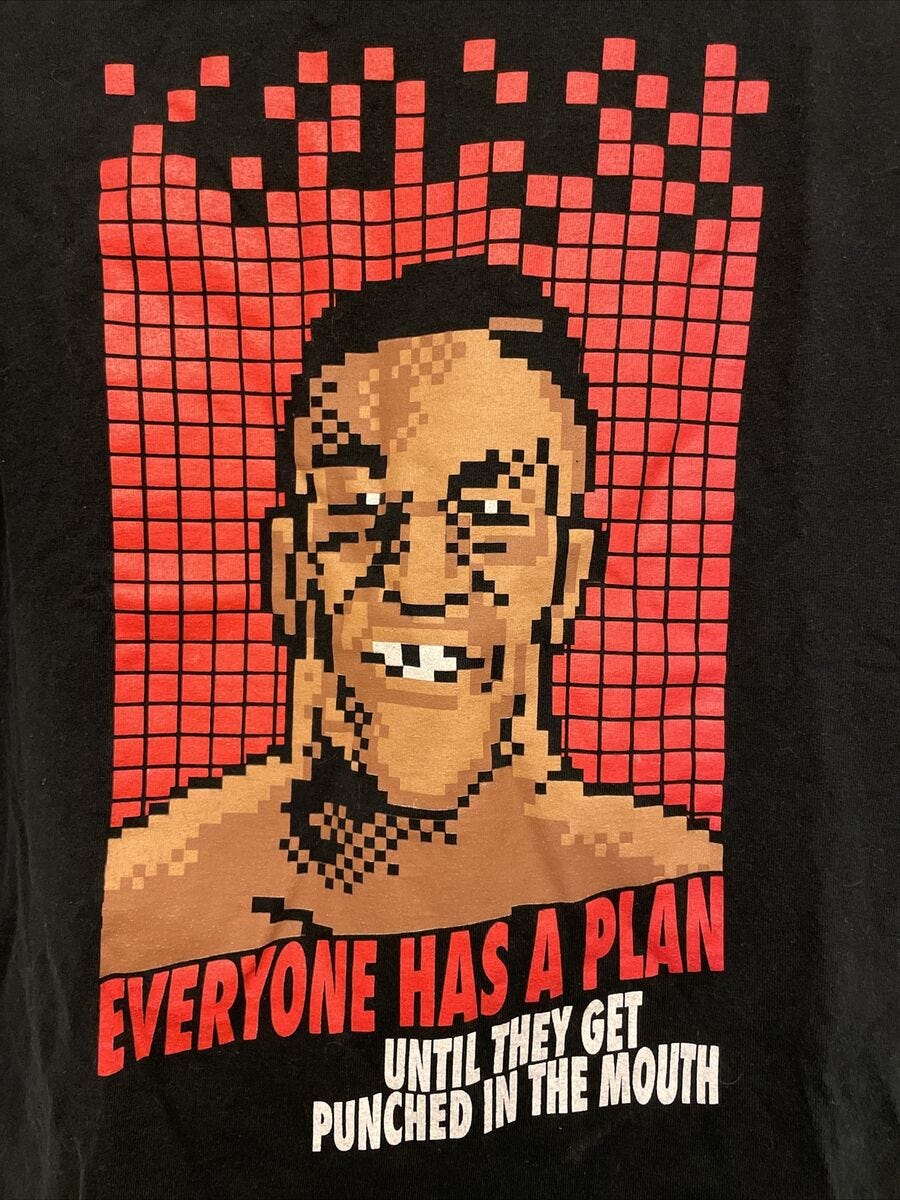

Therefore, Mike Tyson’s theory of everyone having a plan until they get punched in the face, becomes more like a law.

What if there was a way to roll with the punches, and not only fight on, but find new and surprisingly innovative ways to fight back?

Changing Perspective on Objectives

In Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned, Stanley and Lehman challenge society’s obsession with rigid goal-setting, and articulate, test, and argue throughout the book, that true innovation arises not from relentless measurement but from exploration and serendipity.

Their research in evolutionary/genetic AI art and robotics reveals that narrowly focused objectives often hinder progress rather than drive it. They advocate for curiosity, creativity, and the pursuit of “interestingness” over rigid ambition.

The authors are computer scientists, and develop their argument from their research into “non-objective” search algorithms.

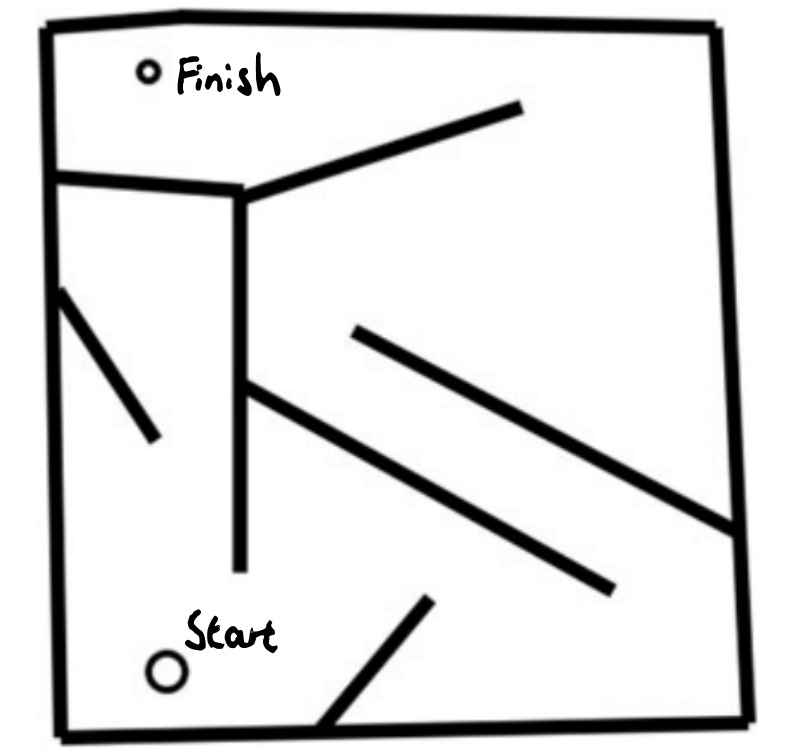

An objective approach to search is goal-directed. Trying to reach the end of a maze, for example, such an algorithm will deem most successful those routes that end up closest to the finish. Mazes, though, are deceptively complex environments — an objective search will often get stuck down blind alleys that leads towards (but not all the way to) the finish.

An alternative is to seek novelty. This way, once an area has been explored (no matter how close it appears to be to the maze’s end), other routes will be sought. This ultimately leads to much more successful maze completion than objective-led searches.

As a jazz musician, this was nothing revelatory. Improvisation, exploration, and serendipity are the heart of jazz, where greatness often comes from unexpected moments rather than rigid objectives.

But as a marketer, the perspective the book brings forth, challenges the way we’ve been trained to think objectively about…objectives.

Marketing is obsessed with KPIs, ROAS, and attribution models—reinforcing the belief that success is a direct result of meticulously measured progress toward an objective.

According to the brilliant research in this book, the greatest innovations typically come from non-objective exploration, not rigid adherence to pre-planned objectives.

What ultimately drives measurable progress may not be what was initially intended for measurement, or even on the radar.

Which brings up what objectives we’re measuring marketing against…

The Problem with Objectives in Marketing

Marketing, business, economic, organizational mindsets can be hotbeds for perverse incentives and misguided metrics.

Here are a few examples from behavioral theory and economics that can help explain:

Campbell’s Law: The more a quantitative metric is used for decision-making, the more likely it is to be corrupted.

If the only goal is high impressions for a campaign, if the traffic is all bots, who cares?

Goodhart’s Law: When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.

If ROI-positive ads are the only thing allowed, other ads that could increase different effectiveness metrics, like price-elasticity or share of market, remain in the dark.

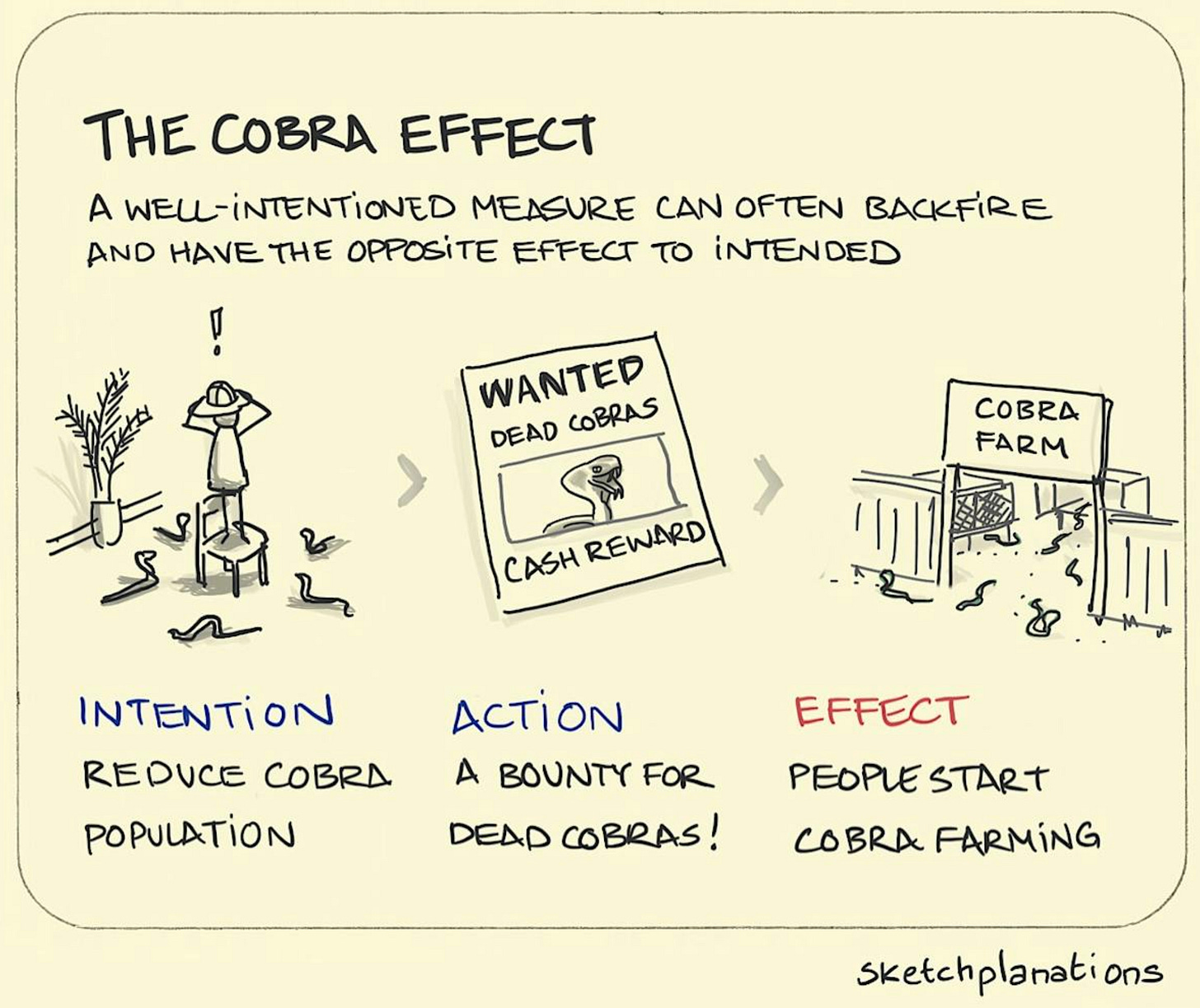

Perverse Incentives (The Cobra Effect): When incentives are poorly structured, they lead to unintended and counterproductive consequences.

Content locking, incentivized app installs, virality through fake followers or AstroTurf reviews.

It’s worth explaining the Cobra Effect in detail to help explain how it works to pervert behaviors and incentive structures.

Economist Horst Siebert coined this term based on a British Raj anecdote. To reduce venomous cobras in Delhi, the government offered a bounty for dead snakes. Initially effective, the incentive led people to breed cobras for profit. When the program was canceled, breeders released the snakes, increasing their population.

Modern examples of the Cobra Effect are printing ghost guns to cash in on a gun buyback program, gig workers revolting against remote monitoring or time-on-task surveillance, or ad budgets needing to be spent entirely in order to be renewed in full regardless of the effectiveness, MQLs that aren’t, inbound that was allbound, last click that was WOM, and funnel cake for everyone.

The Delusion of ROI/ROAS

One of the best examples of a popular objective in marketing is ROI.

Originally developed for manufacturing efficiency, ROI in marketing prioritizes limiting spend rather than measuring true impact. The IPA Databank found that ROI-driven campaigns overemphasize short-term returns, often at the expense of brand value and long-term growth.

I did a ton of research on ROI and was so amazed at the delusional behavior it generates, I wrote an audio dramatic work, “ROI: The Musical” to educate and entertain marketers on this topic.

Similarly, ROI’s twin, ROAS, creates misleading correlations between ad spend and revenue, often encouraging short-term, bottom-funnel tactics that ignore sustainable brand-building efforts.

In Tom Roach’s brilliant take down of ROAS, he articulately explains, ROAS is misleading because it implies a causal relationship between ad spend and revenue that doesn't actually exist. It merely attributes sales to ads shown within a set timeframe, often giving undue credit to the last-clicked platform.

He goes on to explain that flawed metrics like ROI and ROAS also encourages competition between channels rather than recognizing their collective role, like a football manager crediting only the striker for every goal.

Moreover, Tom points out that optimizing for ROAS prioritizes easy, bottom-funnel sales over long-term growth, ignoring the need to engage new audiences who may initially deliver a lower ROAS but are essential for sustainable success.

Heck, even the Director of Planning for Meta just put up a post saying ROAS is overblown.

And if all of this isn’t enough to get you to question the objective of ROI and ROAS, we’ll finish this section with Rory Sutherland’s explanation of the danger behind objective-based thinking in marketing, and his advice on how to spring the trap;

Rory’s powerful observation here is both a warning to the limited thinking objectives can give us, and a clarion call that our subjective thinking is one of the best tools to bring to the table.

Because, if we’re basing our thinking on what other people might be thinking, or wanting us to think; well then we’re in a bit of a jam.

Thankfully, there’s a famous French theologian and literary scholar to our rescue…

The Problem with Personal Objectives

Rene Girard’s Mimetic Theory reveals that desires are shaped by what others want rather than by independent needs.

There are few passages from his seminal work, “Things Hidden Since The Foundation of The World” that are worth including here.

“The value of an object grows in proportion to the resistance met in acquiring it. Even if there’s no prestige to the object, rivalry will bring prestige to the object automatically.”

Explains why people fight over “nothing.” And how we can engineer demand for potentially useless products – the marketer’s ethical event horizon.

“Everyone is opposed to “fashion” – because everyone is endlessly deserting the reigning fashion in order to imitate what has not yet been imitated, what everybody is only beginning to imitate.”

The bleeding edge and change/change/change will always yield some marketable results because new is different is good? Dangerous thinking for longer-term strategies.

“Mimetic context plays a central role in vocations that depend on the judgments of others. Actors, performers, politicians, (marketers) those in direct contact with crowds and live off their favors – How is it possible to distinguish a manic-depressive tendency and the emotions registered by someone whose existence largely depends on the arbitrary decisions that arise from mimetic contagion?

Marketers are constantly making decisions in a vacuum, attempting to engineer desire for the faceless masses or made-up stereo-typical personas, staring at disconnected numbers, living off reports and dying at the whim of “the market.” One day you could make a million dollars or it could all come crashing down, one day they like the ad one day then they hate it, one day the calls are coming in one day they’re not, one day the web clicks are up thanks to a green button one day they don’t like the button and clicks go down. Imagine engineering ads that continue the mimetic struggle, and in turn destroy the marketing eco-system?

Seem a little manic to you? Do you object? Well, what are the objectives?

Realizing mimetic desire affects and intertwines with marketing decisions is important .

If objectives are based on competitive benchmarking, chasing someone else’s definition of a goal, or the next big white whale, businesses risk chasing aspirations shaped by external forces instead of pursuing internally aligned strategies that hold unique value.

If you have a goal in mind, the best way to get there is never clear—if it were, we’d all be there already. The problem isn’t believing a path exists, but rather the assumption that reliable objectives are the only sensible way to chart a course.

What I’m advocating for, and what I hope this research demonstrates, is a reexamination of the many follies that come with an objective-tied mindset, along with an urgency to explore chosen fields and focuses with the same objective-less approach that has driven some of the most innovative ideas in history.

Action Steps: Rethinking Objectives in Marketing

Objectives have their place, but they must be tied to strategic thinking rather than blind adherence to arbitrary or overly ambitious metrics.

Instead of focusing solely on rigid objectives, marketers can feel free to add in ways to measure progress such that it allows for discovery, creativity, and resilience.

The following suggestions can help marketers escape the objective trap:

Embrace Mistakes as Learning Opportunities – Like Stanley and Lehman’s Novelty Search, encourage exploration. Mistakes and surprises often lead to the most valuable insights.

Avoid Mimetic Traps – Trying to keep it real, compared to what? Stop bench marking against competitors and focus on unique metrics that reflect your progress.

Expand Beyond ROI and ROAS – Incorporate multi-metric reporting that makes sense for you that includes Customer Lifetime Value (CLV), brand awareness, and engagement.

Measure the Long-Term Impact of Marketing – Run brand lift studies, track sentiment shifts, and set separate KPIs for brand-building activities.

Adopt an Exploratory Mindset – Shift from rigid goal-setting to adaptive, discovery-driven strategies.

Innovation and growth emerge not from chasing a predetermined target but from engaging fully with the process itself.

Avoiding the pitfalls of objective-based thinking is not about abandoning goals entirely—it is about redefining our behaviors, expectations, and boundaries.

The Marketing Delusion Series

Welcome to The Delusion Series—the no-BS guide to calling out the myths marketers keep telling themselves (and their customers).

Couldn't agree more. Just wish the world around us was more accepting of this approach. Immediate results (aka $$$) determine who gets help and who doesn't. The curious among us are on our own.